To become a successful author of forgeries, which would be difficult to distinguish from real painting masterpieces even for an experienced expert, criminal talent alone is not enough. Triumph in this specific field of activity is made up of various factors, including an analytical mindset, an adventurous spirit, ingenuity and also the ability to get into the shoes of a true artist. And in the postmodern era, the forgery authors sometimes become celebrities themselves: their paintings are exhibited in museums under their own names — though not always for their artistic value.

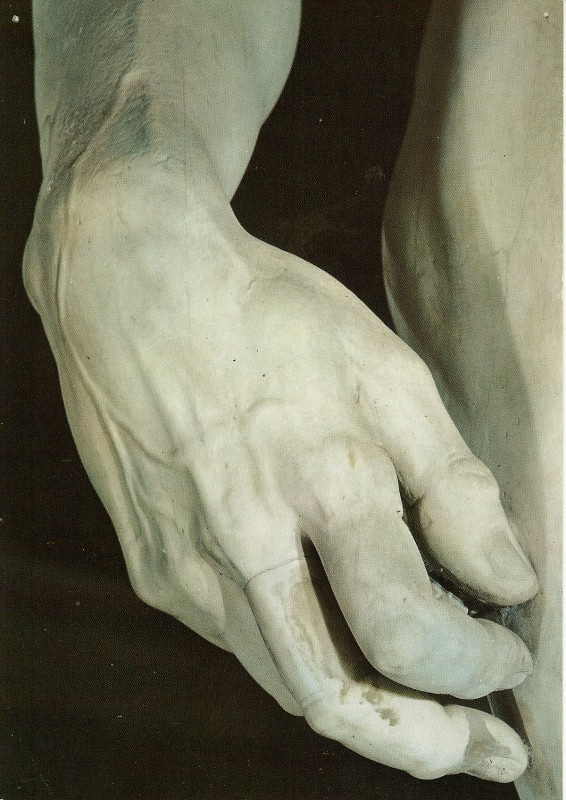

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Before becoming an honoured artist himself, the Italian painter and sculptor made copies. At that time, ancient Roman marble sculptures were highly valued, and, according to the historian Paolo Giovio, Michelangelo was involved in a story with the falsification of such a sculpture.In 1496, he created a marble statue, Sleeping Cupid, and tried to give it an aged look by burying it in the ground. An antiques dealer named Baldassarre del Milanese presented Michelangelo’s "Ancient Roman" sculpture to the attention of Cardinal Rafaele Riario, a great admirer of such works of art. He gladly acquired it, but after a while he returned the sculpture, having learned about its true origin.

The Sleeping Cupid by Michelangelo could look like the Baby Christ in the Madonna of Bruges statue.

It would seem that the case should have ended in scandal at best, and punishment for Michelangelo at worst. But his talent rescued him from the trouble, because while they saw into the "ancient" sculpture, his author’s work, Pietà, which adorned St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, became so popular that the cardinal wanted to regain the ill-fated Cupid. Although he soon resold it, not as a Roman antique however, but as a work of the most popular sculptor in the Italian capital at that time.

Pieta (Lamentation Of Christ)

1499, 174×195 cm

Various biographers of Michelangelo disagree on whether he deliberately went for a deception. Some of them prefer to believe that the authorship of the criminal design belonged to a dealer of Roman antiquities, while others assume that the sculptor was driven by excitement: he wanted to check whether his skill was enough to mislead an experienced collector. Be that as it may, the deceived Cardinal Riario wasn’t angry with Michelangelo, he even ordered him two more works after all the events.

While those who want to believe in the sincerity and righteousness of the painter would not like the words of Vasari who wrote about Michelangelo’s repeated machinations with the works of other authors:

"He also reproduced the drawings by various old artists so similarly that one could be mistaken, because he tinted them with smoke and various other things, giving them an old look, and soiled them so that they really seemed old and, when compared with the genuine ones, it was impossible to tell the difference. And he only did this in order to return the reproduced ones and get the original paintings, which he admired for their perfection of art and tried to surpass with his work, thus gained his widespread fame."

But who will blame Michelangelo for his desperate desire to take possession of the works of his idols now? After all, as usual, the winners are not judged.

"He also reproduced the drawings by various old artists so similarly that one could be mistaken, because he tinted them with smoke and various other things, giving them an old look, and soiled them so that they really seemed old and, when compared with the genuine ones, it was impossible to tell the difference. And he only did this in order to return the reproduced ones and get the original paintings, which he admired for their perfection of art and tried to surpass with his work, thus gained his widespread fame."

But who will blame Michelangelo for his desperate desire to take possession of the works of his idols now? After all, as usual, the winners are not judged.

Hans van Meegeren

Speaking about the forgers of the old masterpieces, we can’t omit the Vermeer's compatriot, who dared to embark on a brave adventure — to reveal to the world as many as seven previously unknown masterpieces of the "authorship" of the painter from Delft. Henrikus van Meegeren was not a particularly gifted artist who tried to build a career creating paintings in the style of old artists like Rembrandt at the beginning of the last century. And although he had some fans among the Dutch nobility, art critics were very sceptical about the work of the unfortunate imitator. Meegeren even conceived an insidious plan of revenge on the art critic Abraham Bredius, who rejected him. He decided to prank his sworn enemy by creating a brilliant counterfeit as if by the recognized artist Vermeer. And when he cannot distinguish his work from the original, Meegeren will disgrace him by announcing his authorship of the pictorial masterpiece. He got hold of 17th century canvas and paints and dared to paint a picture on a religious theme — there were virtually no such subjects among the famous works by Vermeer.

Christ in the house of Martha and Mary

1660-th

, 160×142 cm

The venture was a success: Christ in Emmaus was recognized as an original by Vermeer and made a splash in the art world. That same Bredius was in such a hurry to become the discoverer of the Vermeer’s unknown masterpieces that he did not pay attention to either the dubious provenance of the picture, or to the poor correspondence of Meegeren’s artistic skills to the skill of the renowned painter.

And when the forger managed to bail out a huge amount of money for his work at that time, he could not follow his original plan and succumbed to the temptation to continue creating new hitherto unknown works by Vermeer.

And when the forger managed to bail out a huge amount of money for his work at that time, he could not follow his original plan and succumbed to the temptation to continue creating new hitherto unknown works by Vermeer.

Christ in Emmaus is the first painting by Meegeren, successfully passed off as an unknown Vermeer

He managed to paint six more such canvases, until he was let down by the connection with the Nazis. One of the buyers of Meegeren’s counterfeit Christ and the Sinner painting was Hermann Goering. In 1945, an investigation into the origin of the canvas in the hiding places of the SS Obergruppenfuehrer led to the arrest of the artist, who faced the death penalty for collaborating with the Nazis. To avoid it, Meegeren admitted that he himself painted all the "newly discovered" paintings by Vermeer. He was eventually found guilty of fraud and sentenced to one year in prison, but just a month later he died of a heart attack.

Meegeren at the trial. Photo: kommersant.ru

It is noteworthy that thanks to his scam, the negligent artist still managed to enter the history of world painting. And his first and most famous work à la Vermeer is still exhibited in one of the largest art galleries in the Netherlands, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. In this whole story, only one thing remains unclear: how badly one must want to find new Vermeer’s masterpieces to believe in his authorship; after all, Meegeren’s canvases, no matter how old they seemed, are frankly rough, clumsy. Apparently, vanity and greed were the main accomplices of the most famous forger of the twentieth century.

Meegeren’s Last Supper was sold as a Vermeer painting for $ 7 million calculated as today.

Eric Hebborn

The name of the British artist and art dealer is not as well known as his Dutch counterpart, although he was far more prolific and talented than Meegeren.In his autobiography, Hebborn confessed to creating more than a thousand forgeries, only a few of which were exposed, and the rest can still be kept in the best museums in the world as originals.

A graduate of the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the British School in Rome, he has acquired many useful skills while working as a restorer. Like Meegeren, he was disappointed and angered that in the 1960s his own realistic paintings were not as popular as the avant-garde works of his more fortunate contemporaries. And he began to take revenge on connoisseurs of painting, creating flawless forgeries of the old artists.

Eric Hebborn was a charming man and a real hedonist. Photo: facebook.com

Hebborn was extremely careful and even elegant. He never sold his fakes to those who did not understand art and could not determine the authenticity of the painting. Thus, he gave the experts the opportunity to decide for themselves whether they were buying a fake or an original, and to define the price they were willing to pay.

He claimed: "There is nothing criminal in making a picture in whatever style you choose, and there is nothing criminal in asking an expert what he thinks of it." For this reason, after the exposure, none of the victims of the deception never sued him. Moreover, the confrontation with Hebborn could lead to disastrous consequences for the largest auction houses, which resold his work as original, and some museums still refuse to admit that they have fakes of his authorship, despite the direct statements of the fraudster. He claimed responsibility for the falsification of the works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Pieter Rubens, Giovanni Piranesi, Anthony van Dyck, Camille Corot and other old artists.

He claimed: "There is nothing criminal in making a picture in whatever style you choose, and there is nothing criminal in asking an expert what he thinks of it." For this reason, after the exposure, none of the victims of the deception never sued him. Moreover, the confrontation with Hebborn could lead to disastrous consequences for the largest auction houses, which resold his work as original, and some museums still refuse to admit that they have fakes of his authorship, despite the direct statements of the fraudster. He claimed responsibility for the falsification of the works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Pieter Rubens, Giovanni Piranesi, Anthony van Dyck, Camille Corot and other old artists.

Saint Ivo

1464, 45×35 cm

According to the British art critic Christopher Wright, A Man Reading (Saint Ivo) painting from the collection of the National Gallery, London, is not the 1450 work of Rogier van der Weyden’s studio, but a modern forgery by Eric Hebborn.

Hebborn used real paper and pigments from the era for his fakes, and his drawing skills were so good that they could not reveal him for a very long time. But in 1978, the curator of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC Konrad Oberhuber noticed that two drawings by different painters were made in the same art style and on the same type of paper. According to Hebborn, within 10 years after being exposed, he made and successfully sold another 500 forgeries of drawings by the old artists. Moreover, some art dealers even asked him to "find" certain drawings by old artists, which he forged and then sold to them. "I just don’t think you’ll find an honest man to be a dealer," Hebborn said in the 1991 BBC documentary, Portrait of a Master Forger.

Hebborn’s forgery of the sketch

for Christ Crowned with Thorns by Anthony van Dyck was acquired by the British Museum in 1970. It is now captioned on the museum’s website as "Drawing by Eric Hebborn in the manner of Anthony van Dyck".

On 8 January 1996, Hebborn was found unconscious on the Roman street, where he had lived for the past 30 years. He died as a result of a severe skull injury, but his death was formally investigated and the cause of the injury was not established. Many believed he had been killed by the Italian mafia, with whom he might have collaborated. According to The Daily Mail newspaper, the death of Hebborn was the revenge of some collector he deceived. According to some reports, he even received threats from one art dealer and was afraid of him. A few weeks before his death, the last book, The Art Forger’s Handbook, was published with detailed instructions for creating art in the manner of European classics. Hebborn believed that he used the same techniques as the painters of the past, so this publication is also suitable for studying the style of the old artists.

Hebborn claimed that Annibale Carracci's painting, A Boy Drinking, at the Cleveland Museum of Art was also his work.

Shaun Greenhalgh

The British fraudster, sentenced to 4 years and 8 months in 2007 for trying to sell an "ancient" Assyrian artifact, worked with his family. Greenhalgh ran a fraudulent art deal with his elderly parents. Like the previous heroes, he thus began to take revenge on the art community for not recognizing his artistic talent. The family came up with an ingenious scheme to exploit weaknesses in auction catalogues. So, they acquired a catalogue describing the lots of the 1892 auction in Silverton Park, Devon. Among them were "eight Egyptian figures of stunning translucent alabaster". This vague description allowed Shaun Greenhalgh to create the Princess Amarna statue. In 2003, it was acquired by the Bolton Museum for almost 440 thousand pounds, in spite of preliminary consultation with experts from the British Museum and the auction house Christie’s.

After Greenhalgh’s exposure, Princess Amarna was removed from the Bolton Museum, but returned in 2018 — this time in the forgeries section. Photo: wikipedia.org

The success of the family counterfeits manufacture and sale business was largely due to George, Shaun’s father. An elderly gentleman in a wheelchair made a trustworthy impression on customers. When he reported that the Amarna Princess was bought by his grandfather at an auction in Silverton Park a hundred years ago, experts readily believed that the statue was one of those eight Egyptian figures over three thousand years old from the description in the old catalogue. Under this scheme, the Greenhalgh family has managed to earn more than £ 800,000 over 17 years by selling at least 120 fakes. And according to the investigation, more than a hundred forgeries may still be kept in collections of museums and private collections around the world as original works of art. Among those revealed are fakes of sculptures by Constantin Brancusi and Paul Gauguin, paintings and drawings by artists Otto Dix, Lawrence Lowry, Thomas Moran and others.

Shaun Greenhalgh with his father George. Source: expertmus.livejournal.com

The Greenhalghs failed with cuneiform. Representatives of the Bonhams auction house turned to experts at the British Museum to verify the authenticity of the Shaun’s bas-reliefs "from the palace of an ancient Assyrian king". But experts discovered errors in the writing of the cuneiform text and turned to the Department of Art and Antiquities of Scotland Yard. A year and a half later, the scammers' family was arrested. Shaun’s elderly parents received suspended sentences, and he served almost five years and was released in 2011.

Upon his release from prison, Greenhalgh not only wrote an autobiography, but also received the Critics' Award for Best Art Book in 2018. And in October 2019, he appeared in Made in Bolton, a short documentary series in which he showed the process of creating four "ancient" works of art using traditional materials and methods.

Upon his release from prison, Greenhalgh not only wrote an autobiography, but also received the Critics' Award for Best Art Book in 2018. And in October 2019, he appeared in Made in Bolton, a short documentary series in which he showed the process of creating four "ancient" works of art using traditional materials and methods.

Beautiful Princess

1496, 33×23.9 cm

In A Forger’s Tale, Greenhalgh states that he painted Leonardo da Vinci’s attributed La Bella Principessa (The Beautiful Princess) in 1978 and was allegedly inspired by cashier Sally from a Bolton supermarket.

Lino Frongia

The author of the forgeries that caused the loudest scandal on the market of old artists in the last 70 years (since Meegeren who made bold to imitate Vermeer’s legacy) has not been reliably established. But in the focus of the investigation on several paintings of dubious origin, the name of the Italian Lino Frongia appears.The hunt for "the Moriarty of Fakers", as the press nicknamed the author of artful forgeries of paintings by Parmigianino, Hals, El Greco and others, began back in 2015. Then the French police withdrew Venus painting allegedly painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder from the exhibition in the French Aix-en-Provence. In 2013, the Prince of Liechtenstein paid about 7 million euros for it. Later examination showed that this work was a modern forgery.

Laboratory study

has shown that the pigments in the Venus painting do not correspond to Cranach’s studio, the signature does not belong to the artist, and the craquelure on it shows signs of heating the panel to simulate the effect of antiquity.

A similar situation arose with a portrait of a man allegedly by Franz Hals, which was sold at Sotheby’s for $ 11 million. After experts recognized it as a fake, the auction house returned the entire amount to the buyer. A similar fate awaited Francesco Parmigianino’s painting of St. Jerome, sold in 2012 at the Sotheby’s New York auction. Six years later, laboratory tests discovered modern pigments in the paint layer and the auction house had to compensate the buyer for the full cost of the painting again.

The painting depicting St. Jerome by Parmigianino or the School of Parmigianino cost the buyer 842.5 thousand dollars.

In September 2019, a French court issued an arrest warrant for Italian artist Lino Frongia. He was arrested but released on bail and is still at large. Very little is known about him: he was born in 1958 in Montecchio and graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. His own work, eerie modernist paintings, is not particularly popular with collectors: the most expensive of them was auctioned for only 15 thousand euros. But he achieved great skill in imitating the works of the old artists.

Long before the scandal broke out, curator Vittorio Sgarbi, former deputy secretary of the Italian Ministry of Culture, admired that his friend Frongia had painted Christ so skilfully that a certain Giuliano Ruffini was able to sell the painting to the Correggio Foundation under the guise of the original work of Antonio Correggio. But the artist refutes this information, although he admits that among his works, there are copies of the works of old artists and a painting with Christ in the style of Correggio among them. He stated that he never sold his copies under the guise of real works.

Long before the scandal broke out, curator Vittorio Sgarbi, former deputy secretary of the Italian Ministry of Culture, admired that his friend Frongia had painted Christ so skilfully that a certain Giuliano Ruffini was able to sell the painting to the Correggio Foundation under the guise of the original work of Antonio Correggio. But the artist refutes this information, although he admits that among his works, there are copies of the works of old artists and a painting with Christ in the style of Correggio among them. He stated that he never sold his copies under the guise of real works.

Self-portrait by Lino Frongia, painted in 1989.

However, there is a bad moment with a suspicious canvas in his biography, although not related to its sale. In 2018, Frongia loaned an El Greco painting from his collection for an exhibition in Treviso. But the police arrested the image of St. Francis upon suspicion of a forgery. Despite the fact that the French court refused to return the painting (in the course of the investigation it was transported to Paris), Frongia continued to claim that it was the real masterpiece by El Greco. Vittorio Sgarbi thought the same, which, however, did not prevent him from calling his friend "the greatest living old artist".

One of Lino Frongia’s paintings from 1980 is influenced by the old artists.

The second suspect in this high-profile case was the collector Giuliano Ruffini, who facilitated the way to the market for all the scandalous fakes. He is also still at large, despite a warrant issued by the Supreme Court of Rome. Allegedly, this is due to an unfinished investigation, but it looks like the process is being hampered by some influential outside forces. Given the location, the Italian mafia comes to mind, but even without its participation, too large amounts of money and the reputation of many people are involved: dealers, auction houses representatives, who participated in the large-scale financial fraud.

For some reason, Giuliano Ruffini avoids publicity, and the only known photograph of him dates back to the 1970s. Source: theartnewspaper.com

In order to compensate somehow for the reputation losses due to a series of returns of the sold fakes, Sotheby’s had to buy the American Orion Analytical laboratory, the one that established the dishonest origin of the paintings sold as works by Parmigianino and Hals.

In just one year, the laboratory’s experts analysed works that cost more than one hundred million dollars.

In addition, they are responsible for keeping and maintaining the auction house lots in good condition. But this step is unlikely to change the situation with counterfeit works of art much in the modern art market, as, according to some experts, they make up half of the total number of sold and bought works by old artists.

In just one year, the laboratory’s experts analysed works that cost more than one hundred million dollars.

In addition, they are responsible for keeping and maintaining the auction house lots in good condition. But this step is unlikely to change the situation with counterfeit works of art much in the modern art market, as, according to some experts, they make up half of the total number of sold and bought works by old artists.